The pure art of political leadership seeks credit for all the positive news and makes sure someone else takes the blame for all the negatives. Whether it’s a psychopathic CEO, an incompetent supervisor – or a prime minister – it’s the same skills set: deflection, obfuscation and ensuring responsibility ends up elsewhere, and never lands at your own doorstep.

But there are limits to this strategy: it may take a while for the public to identify the leaders who avert responsibilities but once the public’s lived reality starts to differ from a political narrative and myth making, that’s when all of the problems for a politician start. And, for the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, these are problems that are slowly starting to gain traction.

It has been evident for some time but this federal government behaves like a star chamber: the sitting of Parliament has been withheld, decisions made behind closed doors, scandals swept away or ignored. More recently, Morrison promised full co-operation with the NSW Government’s Special Commission of Inquiry into the Ruby Princess, but then decided to block two federal officials from appearing.

On this occasion, Morrison spoke from both sides of the mouth: initially appearing earnest in his support for an open and honest public inquiry (the good news) but, ultimately, ensuring that there could never be any impediment (the bad news) to his reputation, irrespective of how undeserved this reputation might be.

Listen to the New Politics podcast!

We will now never know, but the appearance of these two federal officials – one from the Department of Agriculture, another from Australian Border Force – must have been so detrimental to the federal government that Morrison had to do everything to block their appearance, even to the extent of forcing the High Court to intervene. We can be assured, however, that this intervention wouldn’t have been the lofty ideal of protecting the independence of the public service.

I’m surprised that the many journalists in the mainstream media waiting on Morrison’s every utterance still haven’t realised that close to everything he says is found to be incorrect – sometimes, even as soon as he makes the statement – and every one of his actions is viewed through a political prism. Of course, politicians are expected to view all of their actions through this prism, that’s the nature of political life: but there are limits.

Problems in aged care

Aged care is a prime example. It’s a piece of bad political luck for Morrison that the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety – established in October 2018 – is being held at exactly the same time as the coronavirus outbreak and related deaths occurring in private age care homes in Melbourne.

Much of the evidence provided to the Commission from a wide range of practitioners and experts in the field of aged care has outlined how many of these current difficulties can be sheeted home to the federal government’s lack of concern in the sector over many years: the already-identified problems relating to staffing shortages and infection control; lack of training; reduced levels of funding.

For those listening into these proceedings at the Royal Commission, the news is often heartbreaking. It’s difficult to accept there are so many gormless bureaucrats and faceless CEOs in the private age care sector, indifferent to the sufferings of the residents in their care, or misguided by their profit motivations for owners and shareholders.

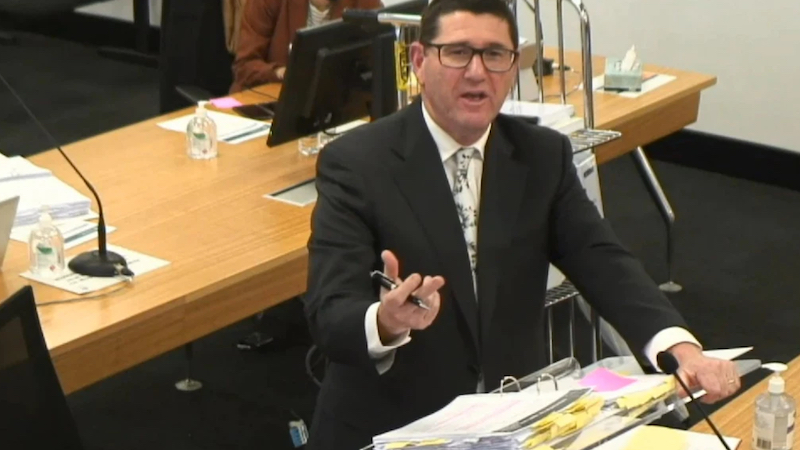

Senior Counsel Assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Rozen QC, announced that the deaths in residential age care from COVID-19, as a percentage of overall deaths from the virus, is now the highest in the world. He expressed his dismay that “the aged care system in 2020 is not a system that is failing. It’s the system operating as it was designed to operate. We should not be surprised at the results”.

It’s a system that needs to change.

Again, Morrison has sought to deflect from these problems – aged care is the responsibility of the federal government – initially blaming the Victoria Department of Health and the operators of aged care facilities. He was also criticised by age care practitioners for not having a strategy for dealing with the outbreak but, again, he went onto the attack, claiming: “there has (always) been a plan, and it has been updated, so we completely reject the assertion that there was not a plan, because there was a plan”.

Support for Morrison’s commentary was also provided by Acting Chief Medical Officer, Paul Kelly: “there’ve been plans in place, specific plans, very detailed specific operational plans for dealing with aged care outbreaks, and preparing for those and ways to prevent them since the middle of March”.

These “very detailed specific operational plans” were so flawed that in the case of St Basil’s Homes for the Aged in Melbourne, there was a four-day delay in the response to their coronavirus outbreak. These plans also resulted in the lack of clarity of whether facilities should prepare for a 30 per cent loss of staff, or a complete loss of staff, and what they could do in this event. And, tragically, these plans have resulted in the deaths of over 200 people in aged care facilities.

Whether there were ‘plans’ in place or not is immaterial: clearly the plans did not have the desired effect and have resulted in a disaster in aged care homes. Morrison was so concerned about the appearances of having a plan, irrespective of how inadequate they were, that he completed overlooked the tragedy of the many deaths that had occurred.

Duplicity and denial

Morrison also has form when it comes to duplicity and contradicting the reality in the aged care sector. As Treasurer, Morrison implemented cutbacks of $1.2 billion to aged care services in the 2016/17 Budget but strenuously denied cutbacks had ever been made, even pushing the argument he’d actually increased funding by $1.2 billion (we’ve reported elsewhere the extent to which Morrison denied cutbacks, even though they are clearly stated in the 2016/17 budget papers).

But denials and reality occupy two different worlds. My father was in a privately-owned aged care facility for two and a half years. It’s a modest facility in suburban Perth and, at the time, it was well-managed, the food was basic but wholesome, and reasonably well staffed.

It was noticeable from the first day of 2017 – when the cutbacks commenced – staffing levels at this facility dropped off, the quality of food deteriorated dramatically, plastic cutlery and paper plates were introduced – inadequate and unusable for many residents – and a generally positive environment was replaced with an atmosphere of doom, gloom and death. My father died six months after these cutbacks were implemented.

Life of course, is finite, and the cutbacks can’t be blamed directly for my father’s death. But his life would have been far more tolerable in those final months if those cutbacks were never implemented. Clearly, the $1.2 billion reduction was made, and had a tangible effect at the grassroots levels for many of these aged care services.

It is possible for a political leader to occasionally obfuscate or issue denials about one matter or another but once this becomes a habit that affects many different areas within the community and the public realises the disparity between their day-to-day real-world experiences and the unbelievable nature of his public commentary, Morrison’s political career is over.

The evidence from the West

This is the exact experience of former Western Australian Premier, Colin Barnett. The public was force-fed a litany of mistruths about a brilliantly performing economy, but this rhetoric wasn’t matched up with the lived experiences of the public: people were losing their jobs, factories were closing, the mining boom had ended with nothing to replace it.

The result for the Liberal Party in the 2017 WA election was a 12.8 per cent swing against it, one of the worst defeats for a sitting government since federation.

Barnett became the leader who was unbelievable and the public could see right through the fabrications and political spin. And once this factor set in, there was no turning back for Barnett.

Morrison is closing in on the same point reached by Barnett in Western Australia. His political instinct is to blame shift, deny responsibility, fabricate material or, in some cases, completely disappear from the national stage for many days.

It was instructive several weeks ago, when the depth of the coronavirus crisis in Melbourne was becoming evident, Morrison was reported as “cutting short” his political tour of Queensland, as if he was the leader of a far-away country or a United Nations’ envoy, interrupted by a nuisance calamity and coming in to inspect the damage in the realm.

The former NSW Premier, Bob Carr, had the habit of seeking credit for good news; blaming bureaucrats or someone else whenever the bad news bubbled to the surface. Carr was Premier for ten years and, at the time of his departure in 2005, NSW was lagging behind many of the other states in terms of economic performance, employment participation, infrastructure funding and investment opportunities. It wasn’t quite a basket case, but almost.

Carr’s longevity in politics says much about his political and media management skills, as well as the luck of having an inept Liberal–National Party in Opposition for most of that time. Longevity is one marker of leadership but so is performance in office, and Carr’s legacy is one of low achievement that also left a pathway for his ministers, Eddie Obeid and Ian McDonald, to engage in corruption and theft of public monies on a grand scale.

Morrison’s strategy is similar to Carr’s. He’s an occupier of the seat of government, rather than a creative producer of great ideas in the public interest; vested interest is the main game, and a wide selection of ministers and backbenchers wallow in a sea of corruption and rorts. Ultimately, like Bob Carr’s NSW Government, there will be nothing to show from a Morrison government and the public will look back and wonder what it was all about.

The ongoing blame-shifting, political stunts and disappearing acts when a crisis erupts is becoming tiresome, and the patience of the public is beginning to wear thin. As Colin Barnett discovered in Western Australia, once the mismatch between rhetoric and reality sets in, there’s no point of return.

It might not be perceptible right now, but it may already be too late for Scott Morrison to turn this around.

Support independent journalism and get a free book!

We don’t plead, beseech, beg, guilt-trip, or claim the end of the world of journalism is nigh. We keep it simple: If you like our work and would like to support it, send a donation, from as little at $1.

And if you pledge $50 or more, we’ll send out a free copy of our new book, Divided Opinions, valued at $27.95.